The earliest surviving directorial work of Fritz Lang, The Spiders, a two-part adventure epic, stands with Lang’s great later work like Dr Mabuse, the Gambler(1923), Metropolis (1926), and Spione (1927) as a wellspring of pop-cultural definition. Here are the common roots of the serials made by Republic Studios, James Bond, Indiana Jones, and just about any other adventure movie where a dashing hero battles gangs of evildoers, trots the globe, and makes escapes by the skin of his teeth. Translating late Victorian and Edwardian Boy’s Own pulp into cinematic terms, and clearly inspired itself by Louis Feulliade’s serials like Fantomas(1913), Les Vampires (1915), and Tih-Minh (1918), The Spiders nonetheless carved out new territory, through Lang’s greater scope of action and peculiar flourishes in creating escapism for a post-War world. Already present are Lang’s pet themes of insidious and conspiratorial forces, solitary and assailed heroes on the hunt for founts of purity, and pulp storytelling dusted with a numinous gleam of otherworldly beauty and threat: surrealism is even more nascent here than in Feuillade's. The hero is Kay Hoog (Carl de Vogt), a reputed gentleman sportsman of San Francisco who has a quest thrust by fate right in his lap, when he finds a message in a bottle sent by a Harvard professor – whose death is glimpsed at the outset – who’s gone missing in South America, claiming to be captive of a lost Incan tribe that lives by a “Golden Lake,” and guards a fabulous cave of less metaphorical gold. Hoog sets out to track down the Golden Lake, but doesn’t know that one of the society guests he recounts his discovery to, Lio Sha (Ressel Orla), is a major figure in the international crime syndicate known as the Spiders, who leave a dead, petrified Tarantula as their calling card.

Even folks who find the pacing of silent cinema awkward could surely lap up the first half of The Spiders, which rockets at a pace any contemporary blockbuster director could appreciate - faster indeed, as Lang has no need to pay heed to today's expected niceties of set-up - whilst maintaining a tightly focused and controlled sense of storytelling that defines the elemental appeal of such rollicking cinema. Within minutes, Hoog is thrust into danger as he travels to South America, whilst Lio Sha pays the denizens of a seedy tavern to kill him: pure coincidence sees Hoog enter the tavern, recognise his danger, and bail everyone up with two trusty six-shooters. Then Hoog takes off on horseback, pursued by his foes, finally grabbing on at the last second to a rope trailing from the hot air balloon of an explorer friend – a great moment of pure cliffhanger pizzazz. Hoog hops off the balloon in the middle of the jungle, close to the land of Incan tribe and the Golden Lake, where the tribe’s anointed “Sun Priestess” Naela (Lil Dagover) swims each day in solitude as part of her ritualised existence. Anticipations here of Lang’s UFA stablemate and rival F.W. Murnau’s Tabu (1931) as untouchably pure maiden entices cultural breach and rupturing worlds, as well as the Edenic glades where Siegfried battles the dragon in Die Nibelungen (1924). Freudian symbolism ignites as Hoog saves the virgin from a lurking snake. Naela returns the favour by hiding Hoog from her tribal fellows by taking him to her private, sacred grotto (more Freudian symbolism?) where a hidden waterfall hides the sunken path through to the cave of gold. In hot pursuit of Hoog, Lio Sha is captured by the Incans, and intended as a sacrifice which Naela will be forced to perform, in order to reawaken the great Incan empire.

Lio Sha is clearly moulded in the image of Feuillade’s Irma Vep and Diana Monti, nominally a wilful, exotic Chinese dragon lady, but with Orla scarcely made to look Asian as Lang makes the play-acting obvious (interestingly, Lang’s Japonaise work, Harakiri, was released between the two episodes of The Spiders). None of the other Spiders, not even ingenious safecracker Four-Finger John (Edgar Pauly), come close to her for dominating the narrative, and Orla projects a marvellously imperious arrogance in the part, although Lio Sha never quite takes on the grandeur of Feuillade’s femme fatales, except at a crucial narrative juncture. Hoog saves Lio Sha – he’s too much of a gentleman to let that sort of funny business stand – and the first episode climaxes in a superbly orchestrated sequence as Lio Sha’s men break into the temple and battle with the Incans, before they break into the gold cave, only to bring about their own destruction by accidentally flooding the cave, whilst Hoog and Naela escape. Tragedy awaits however, as Lio Sha survives the deluge, tracks Hoog back to San Francisco, where she tries to command Hoog’s affections, only to be rejected in favour of Naela, sparking Lio Sha to terrible revenge, having Naela assassinated. Hoog is bereft and vows his own campaign of destruction against his enemies.

Lang had been forced to pass on directing his script for Das Kabinett des Doktor Caligari (1919) because he was committed to make this, which was intended to be a four-part epic in a manner not that different to modern franchise epics. Lang’s early technique is lucid and simple for the most part, but hard-paced and occasionally confirming the presence of a great cinema pioneer at the helm throughout. Lang’s fascination for deliberately static, two-dimensional framings in the stage-like manner of very early films and utilised often in Dr Mabuse and Die Nibelungen, is mostly absent here, placing less emphasis on mise-en-scenethan on shot-for-shot rhythm, as appropriate for this mode of storytelling. And yet Lang’s gift for visual constructs that replicated design effects and assumptions of Cubist and other early-modern art forms is apparent in the Incan temple, a conglomeration of gigantic blocks and rectilinear shots that emphasise ritualism in the posturing of a gaudily attired Naela, seated above the Incan high priest as he orchestrates Lio Sha’s sacrifice. He conjures clever visual exposition devices and quirks, opening with Lio Sha and the other club guests expecting Hoog’s arrival for a yacht race and instead treated to his tale of discovery, explicated through flashback. A later sequence offers a seer trying to trace the history of a missing diamond that traces the faces of each generation of a family through to the present. Lang also makes a lot of use cross-cutting, some of it rough, as the rules for smoothly shifting between scenes still seem happenstance, but still maintaining coherency. A level of self-mockery is also apparent, in a manner anticipatory of the pulp satire of decades to come like Get Smart, as Hoog stows away aboard a Spider ship inside a large crate that is equipped with all the creature comforts, including an electric light, nice wine selection, and a well-stocked library.

All of this gives flesh and verve to the free-form narrative which takes the notion of the underworld to an extreme that anticipates a frightening number of later connections, from Confessions of an Opium Eater (1962) to Big Trouble in Little China (1986) to Guillermo Del Toro’s delight in worlds within worlds, as Hoog tracks the Spiders down into an “underground Chinese city” that’s been constructed beneath San Francisco. The underlying racial politics in the pulp tale are odd and blurred. The discovery of the Incan tribe and Naela’s image of unspoilt pagan beauty feels of a unit with early twentieth century German fascination for the spiritual purity of the noble savage (see also Carl May’s Winnetou stories), certainly cross-breeding with Lang’s own fascination with the mystique of the Edenic, from which civilisation represents an inevitable fall into human depravity wrought by intense emotions, a drama enacted in spare and personal terms by the Hoog-Naela-Lio Sha drama. This coexists with hints common to a lot of pulp of the period (see also Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu novels) at an insidious erosion of white western dominance and attempts by other races to achieve dominance, as the Incans seek renewed power, and the Spiders’ Hindu helpmates who want to throw out western imperialists, whilst the Chinese quite literally undermine the American city. But Lang emphasises the apolitical, multinational Spiders as a manipulative pan-global conspiracy, with meetings between their members a gallery of suited Europeans and more colourfully attired Asiatics, who seek to turn the dream of Asian independence to their own tyrannical ends.

Much of The Spiders’ ingenious and exotic landscape accords with Lang’s interest in creating worlds as psychological expressions, turning his San Francisco into an early variation on the collapsing Weimar of Dr Mabuse, the forest/city schisms of Die Nibelungen, and the multifarious zones of Metropolis and The Tiger of Eschnapur/The Indian Tomb(1959) with underground chambers filled with sealed-off terrors as literalised id, to accompany the dreams of transcendence expressed through skyscrapers in Metropolis and here in the Golden Lake. The Spiders clearly anticipate not just Lang’s own criminal cabals in Dr Mabuseand The Big Heat (1953), but SPECTRE in the Bond films and every other menacingly named villainous organisation in cinema, TV, and comic books to come in the following century. Reference is made to Lio Sha’s overlord, a mysterious unseen Leader, a spidery presence at the centre of all. The driving tensions between the familiar and stable and the threatening and corrosive are arranged along a new-old axis, as is so often the case in the Bond films, with the Spiders meeting in sealed underground chambers walled with smooth steel, where Lio Sha keeps an eye on them with something very like a television, establishing the film however vaguely within the realm of science-fiction. Hoog lounges in his spacious Victorian manse, an icon of leisured, moneyed privilege who deigns to combat evil anyway, thereby adding Batman to his list descendants. Hoog’s campaign to bust the Spiders sees him track down the hidden headquarters and help the police in raiding it, parachuting onto the roof from a buddy’s plane and penetrating the inner sanctums, but missing Lio Sha.

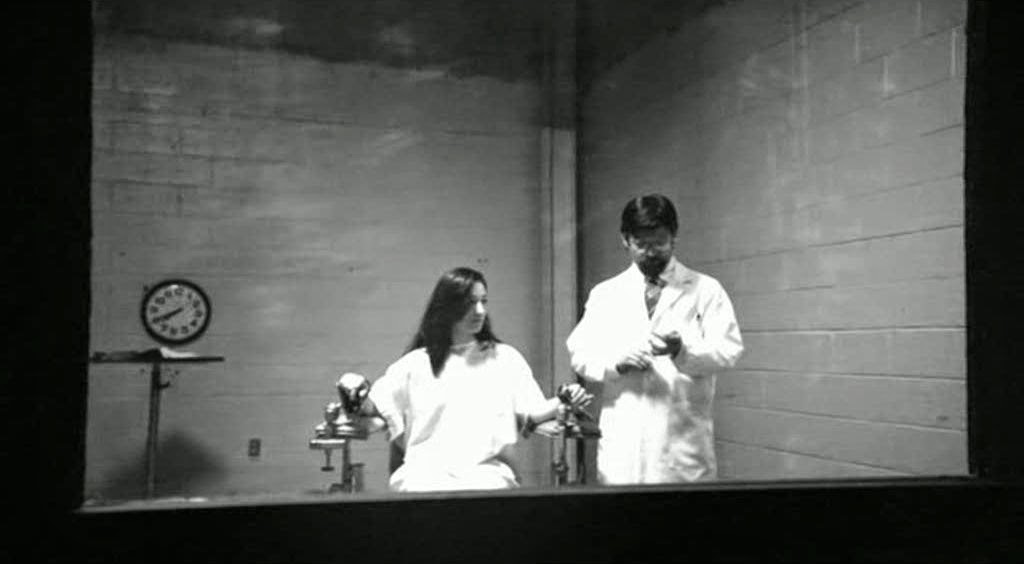

The second half is much more fitful than the first, lacking its compulsive pace and flagrant inventiveness, although the early scenes of Hoog’s campaign against the Spiders and penetration of the Chinese city suggest no fall-off in imagination. The story this time around, as diamond magnate John Terry (Rudolf Lettinger) is targeted by the Spiders because his family own the “Budda-Diamond”, a totem that will drive the Diamond Ship, although what the Diamond Ship is remains frustratingly unexplained and unexploited. The narrative instead steadily loses steam as Terry’s daughter Ellen (Thea Zander) is kidnapped for blackmail, whilst Hoog is forced by Lio Sha to take her and her henchmen to the Falkland Islands, where he learns the Budda-Diamond is buried. A splendidly overripe flashback to the Terrys’ pirate ancestor and his crew burying their treasure there doesn’t compensate for a narrative quickly steam, with a rushed, deus-ex-machinacomeuppance for Lio Sha, sparing Hoog any unsporting gestures, before as easy rescue for Ellen from the clutches of the Spiders’ hypnotic genius Dr Telphas (Georg John). It’s quite clear then why Lang abandoned the project well before its projected completion, as he lost interest in thinking up more elaborate thrill situations with the grand staging of the first half lapsed into cramped situations. On the other hand, here Lang is clearly straining to create a different kind of dramatic thriller touching on Dr Mabuse’s and Metropolis’ fascination with mental domination and more intimate tyrannies: the only thing eluding him here was the ability to create more complex psychological settings in this straightforward context. In spite of the wane in the last third, The Spiders is still a hugely enjoyable and ebullient marvel that genuinely bridges the very last days of cinema’s infancy and the onset of its new maturity.